chron.com

By Bob Cooper

January 30, 2014

Each night during Carnaval, a river of humanity flows onto Mazatlan's malecón.

The

world's longest uninterrupted promenade, curving beguilingly for four

miles on the Pacific, is taken over nightly by families and

dressed-to-kill singles for a week-long blur of parades, concerts,

beauty contests and fireworks. Shrimp is grilled and margaritas mixed on

street corners where mariachi bands brass up the mood. Music, food

smells and celebrants spill out of the restaurants, nightclubs, bars and

small hotels. The spectacle repeats itself for the 116th year on Feb.

27 to March 4.

Rio's Carnaval and New Orleans' Mardi Gras

are better known worldwide, but the world's third-largest such festival

in Mazatlan draws more than 600,000 people for the Sunday parade - the

largest event among many. Most are from Mexico, but many visitors also

arrive from the U.S., Canada and other Latin American countries. The

tradition, a "last hurrah" before Lent begins on Ash Wednesday,

commenced in Mazatlan in 1898. A heavy police presence ensures that the

potent mix of crowds, street music and Pacifico beer, which flows

nightly until 4 a.m., is remarkably peaceful.

"Put that many people in that small a space with all that alcohol in America, and you'd have problems," says Kurt Miller,

53, an Oregon truck stop owner who spends several weeks a year at his

winter home in Mazatlan with his wife, P.J. "But at Carnaval, everyone

gets along and has a good time." At his first one, he sat with Mexican

friends and their 60 extended family members - grandparents, uncles,

aunts, cousins. "It's a huge part of the culture."

Culture and

tradition share equal billing with food and beverage at the three-ring

circus that is Carnaval. The baseball stadium is transformed into a

sold-out concert venue, with nightly themed performances by the region's

opera, ballet, symphony and dance companies.

-On the night I attended, dance troupes accompanied by a full orchestra and chorus performed show tunes ("Mary Poppins"

songs are just as delightful in Spanish). Seniors and couples filled

the stadium seats, while los niños in centerfield folding chairs chomped

away on churros.

The beauty contest the next night on the malecón

is another crowd favorite. Most of the stiletto-and-gown-wearing

contestants vying for Queen of the Carnaval were teens from cities and

states around Mexico, but one arrived from Ecuador and two from Southern

California. By custom, most were dutifully escorted to the stage by

their mothers.

The ceremony was followed by a massive fireworks

and searchlight show, with flares fired from the beach and from boats

docked offshore above the C-shaped bay. Hip-hop, classical and Mexican

hits boomed from speakers all along the seawall, with the beat

coordinated to the explosions in the sky.

I expected families at

the children's dances the next day, but not at the bullfight. This

tradition, too, is revered by Carnaval-goers of all ages. It begins with

preliminary bouts-a flurry of pawing, snorting, charging and ultimately

collapsing bulls.

It wasn't all one-sided last winter, as one

picador was gored and limped off after brushing too close to a bull's

horns. Finally the crowd roared their approval when the horseback

headliner strutted out. Spaniard Pablo Hermoso is the Rafael Nadal

of rejoneo (bullfighting on Arabian horses), and he displayed the skill

of a champion athlete in his deadly dance with the bull, Gitano. After

much taunting, Gitano was soon vanquished, roses were tossed into the

ring and mules were summoned to haul off the body. Bullfights, I

learned, are an acquired taste.

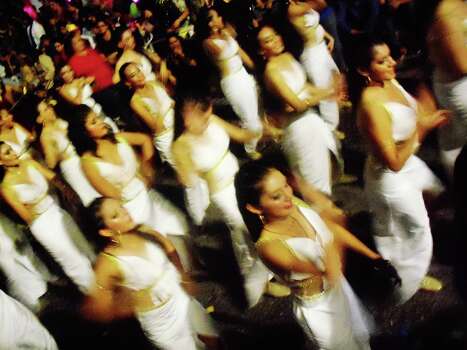

It's the parades that have been

Carnaval's signature events ever since decorated bicycles and horse

carriages enlivened the malecón route in 1898. Now mounted on trucks,

the floats are creative and lavish, flashing with multicolored lights,

thumping with banda music (the region's odd blend of mariachi and German

polka) and jumping with costumed - and barely costumed - singers and

dancers. In one float, a chorus of beaming grandmothers sang, danced and

waved to the Sunday parade throng, which far exceeded the 440,000

population of Mazatlan. On the sidewalks, vendors sold light sticks and

toys to the kids, and masks, rainbow-striped Afro wigs and bead

necklaces to adults.

"We really enjoy watching the cultural shows, the crowning of the child queen and the fireworks," says Steve Backman,

53, a chiropractor from California who settled with his wife and three

daughters in Mazatlan seven years ago. One of 7,000 expatriates from the

U.S. and Canada who reside year-round in Mazatlan, he heads up Friends

of Mexico, which provides scholarships and school supplies to local

students. "Unlike New Orleans and Rio, Mazatlan celebrates Carnaval with

a family atmosphere," he says, "plus a lot of beer thrown in."

Once

the last of the floats, bands and dance troupes complete the parade

route, spectators wander back to their buses, cars and colorful pulmonia

cabs (picture the lovechild of a golf cart and a Manila Jeepney), or

to restaurants, bars and hotels to celebrate longer into the night. Most

return to the scene on Fat Tuesday, the traditional final night of

Carnaval, for one last parade, one final blowout of color, sound and

motion. Then it's back to normal until the same time, next year.

Bob Cooper is a freelance writer.

No comments:

Post a Comment